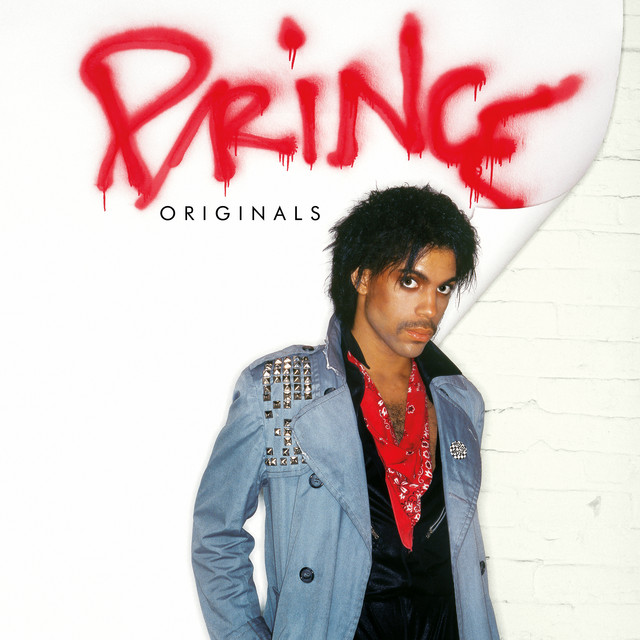

Prince’s ‘Originals’ Gathers Blueprints of His Handed-Off Hits Songs branded by the Bangles, Sinéad O’Connor and others, sung by the gender-bender who wrote ‘em

Prince in the early-to-mid Eighties was spitting out hot songs at such a clip, it’s no wonder he shared the wealth. And wealth it was: his “Manic Monday” was the Bangles’ first hit, reaching Top Five in the U.S., while Sinead O’Connor never had a more successful song than “Nothing Compares to U,” a near-global Number One. Prince’s overflow songs also functioned as brand extensions, especially when covered by acts in his creative camp: Vanity 6, Apollonia 6, the Time, Sheila E. Originals, the latest release from Prince’s vaults (see Piano & A Microphone 1983 and the posthumous Anthology 1995 – 2010), demonstrates that he wasn’t handing off sketches. It collects Prince’s own versions of these songs, all fully-formed. Many, in fact, in their instrumentation and arrangements, are nearly indistinguishable from the gifted versions. The opener, “Sex Shooter,” mirrors the Apollonia 6 performance in Purple Rain and on the group’s debut, with minor lyrical rejigging. “Jungle Love” is a near-Xerox of the Time’s, down to the monkey noises and the “oh-way-oh-way-oh” backing vocals. “The Glamorous Life” begins with apparently the same unhinged sax and funky cello as on Sheila E’s signature, and proceeds similarly, omitting little besides the five-minute drum fireworks coda. The 15 songs range from entertaining throwaways to top-shelf Prince, making this basically a very good golden-era Prince album, with material recorded entirely between 1981-85 but for the ’91 version of “Love… Thy Will Be Done,” a hit that year for Martika. Will Hermes 'Prince's Originals is a unique look into the late artist's songwriting prowess By Alex Suskind June 21, 2019 at 09:12 PM EDT Posthumously released work rarely lives up to its potential. Thankfully, Prince left fans with more than just a series of undercooked one-offs. The second LP released since his death in 2016, Originalsis made up of demos of songs the Purple One wrote for other artists — from the glossy upscale dream of “The Glamorous Life” (famously sung by Sheila E.) to the call-and-response funk of “Jungle Love” (the Time) to the poppy workweek blues of “Manic Monday” (the Bangles). There are several versions of the late artist on display: Rock Star Prince, Sexed-Up Prince, Falsetto Prince. But it’s Songwriting Prince who takes precedent, revealing (with a few outliers) how little the artists strayed from the actual blueprints. The gospel outro of “Love… Thy Will Be Done” (Martika) and the slow-burn groove of “Baby, You’re a Trip” (Jill Jones) remain intact, save for the vocals. That makes Originals' exceptions all the more potent. Prince’s deep voice on “You’re My Love” and the pumped-up groove of “Wouldn’t You Love to Love Me?” help surpass the songs’ future selves by Kenny Rogers and Taja Sevelle, respectively. Same goes for “Nothing Compares 2 U” (the Family/Sinéad O’Connor), with its charging guitar riffs and syrupy saxophone. It all makes for a powerful listen and further proof that if there’s bad music inside the Paisley Park vault, we’ve yet to hear it. A-

THE GUARDIAN 4 stars (out of 5) Laura Snapes | Fri 21 Jun 2019 05.00 EDT For Prince, writing for other artists was a way to proliferate his musical influence and secure his legacy. (Depressingly, his closest modern analogue in that respect is Ed Sheeran, a man spreading a considerably thinner gift thinner still.) Originals, a collection of Prince’s guide demos for his funk proselytisers, shows the breadth and brilliance of his compositional talents – and also the judiciousness underpinning his own catalogue. It unspools like a greatest hits, even though few of the songs included were proper hits: the Bangles sell Manic Monday better than Prince does (bearing in mind these scratches weren’t made for public consumption), largely because you believe Susanna Hoffs actually understood the workaday grind, and Prince sounds miffed by the very concept of it. His Nothing Compares 2 U coexists beautifully with Sinéad O’Connor’s version, finding hope and sensuality where she saw devastation. And he could easily have transformed some of the other tracks into chart fare: Jill Jones’s coquettish Baby, You’re a Trip pales next to his church organ-battering, throat-shredding psychedelic rhapsodics, and he pushes Holly Rock into more daring, vivacious territory than Sheila E did. He also shows up Kenny Rogers’ pale take on You’re My Love, sinking to deeper, soul-stirring notes almost worthy of Barry White. Sometimes Prince’s limitations are revealed: he’s no match for the deliciously supercilious Vanity 6 on Make-Up, and adds too much gothic melodrama to Noon Rendezvous, bettered by a suitably crushed-sounding Sheila E. But still – he wrote these songs, a fact that Originals drives home with his trademark casual confidence. Prince – ‘Prince: Originals’ review 5 stars (out of 5) By Thomas Hobbs | 13th June 2019 Capable of upstaging Eric Clapton on guitar, releasing powerful pop that toed the line between apocalyptic and sexy, and contorting his voice to do just about anything, there was no limit to Prince’s abilities. But not everybody is aware the purple one was also a prolific ghostwriter, penning hits for everyone from The Bangles to Kenny Rogers and Stevie Nicks. New posthumous album ‘Prince: Originals’, which has been released by the Prince Estate in collaboration with Warner Bros and Jay-Z’s streaming platform Tidal, has raided the vaults of Paisley Park to bring together 14 reference tracks Prince laid down for other artists, with this collection acting as a fascinating time capsule of the 1980s. Prince nails the deep nasally vocals of a country singer on ‘You’re My Love’, a track he tellingly penned for Kenny Rogers, while his effeminate vocals channel the experience of being an independent black woman on ‘The Glamorous Life’, the hit single he wrote for frequent collaborator Shelia E. Hearing. Prince, singing two songs that are so different stylistically, reminds us just how insanely talented he was, with the artist possessing a chameleon-like ability to master practically any genre of music. ‘Prince: Originals’ is at its best when Prince lets loose and embraces his cheekier sider. The phallic symbolism of ‘Sex Shooter’, which contains the playful lyrics “I need you to pull my trigger babe / I can’t do it alone”, is one hell of a ride, while the absolutely bonkers ‘Holly Rock’ sees Prince talking slick over a beat that sounds like it was crafted from a psychedelic pinball machine. Honestly, it’s a shame Prince ever gave these tracks away to other artists. Although the camp synths and indulgent guitar solos present on a lot of these tracks are clear by-products of the decade that gave us cone bras, Super Mario and The Goonies, this music also sounds prescient, with the raw experimental funk of ‘Wouldn’t You Love To Love Me’ (written in 1981 for singer Taja Seville) sounding like it would be right at home on bold 2019 releases such as Tyler, The Creator’s ‘Igor’ and Steve Lacy’s Apollo XXI. The fact you can hear Prince so obviously channeled when listening to these two modern black artists is a powerful reminder of just how ahead of its time his music was. A lot of the songs on this collection have a playful innocence to them and it’s clear Prince enjoyed writing music for other artists, seeing it more as an opportunity to be experimental and loose, rather than a coldly technical chore. You can almost feel the beaming smile Prince was rocking while singing the original ‘Manic Monday’ (the smash, which he penned for The Bangles, is one of the highlights here) while ‘Jungle Love’ (a hit Prince wrote for The Time) is reflective of an era where music was about making you dance first and think second. Both tracks are infectiously joyous, and if this collection is any indicator of the quality of the thousands of hours of unreleased music Prince still has in the vaults, then don’t be surprised if we’re still partying to new Prince music in 2099. PITCHFORK by Rebecca Bengal | JUNE 7 2019 Hearing Prince sing these songs that he gave to other performers brings you close to the pulse of his artistry: transgressive, funky, sexy, a testament to his genius even in the form of demos.It was said that only Prince knew the combination to his legendary, quite literal vault with the spinning wheel doorknob. But sometime after his death on April 21, 2016, the hulking door was drilled open, revealing an astounding archive of unreleased songs—so many thousands of tapes and hard drives that his estate could allegedly release a Prince album every year for the next century. Now, the latest from the vault, comes Prince: Originals, a compilation of 14 previously unreleased songs written for other performers that prove once and for all that a Prince demo was often better than most other musicians’ finished songs. It offers a window onto the playfulness of his improvisations and, in a structure that mimics the range of an actual Prince album, shifts nimbly between up-tempo songs and ballads, sweat and tears, near impossible to stay sitting still while listening. In the winter after the release of his third album, Dirty Mind, 22-year-old Prince moved into what he’d call Kiowa Trail Home Studio in suburban Chanhassen, Minnesota, not far from what would become Paisley Park. Prince had its cream-colored exterior repainted with his favorite hue; it was nicknamed the Purple House. Outside was the driveway where he’d do motorcycle laps practicing for Purple Rain and the gates he decorated with a sculpted heart and peace sign. Inside, he outfitted his studio with a 16-track recorder and later upgraded to a 24-track Ampex MM1200, with a piano upstairs for any sudden inspiration. Inside the Purple House, large parts of Controversy, 1999, Purple Rain, and Sign o’ the Times were recorded, as well as about half the songs on Originals (most of the rest were recorded at Sunset Sound in Los Angeles). In 1985, when he sat with a Rolling Stone reporter on the white plush carpet of the bedroom at Kiowa Trail, he said that he finally came to understand why his musician father was so hard to live with. “When he was working or thinking, he had a private pulse going constantly inside him,” Prince said. “I don’t know, your bloodstream beats differently.” Discovering some of the unscripted moments in Originals feels like taking that pulse. Written into his Warner Bros. contract was a clause that allowed him to recruit and produce other artists. It essentially assured him access to a congregation of performers who would spread the gospel of his music—the pop-funk he’d canonized in his early records, and a vast and uncharted road ahead, both under his own name and others. Sometimes he adopted an alias—as Joey Coco, for instance, for the power crooner “You’re My Love,” one of the surprises on Originals. It appeared on Kenny Rogers' 1986 album They Don't Make Them Like They Used To, but Rogers’ version pales next to Prince’s, who uses a deeper, full-throated register that sounds an imitation of what he thought Kenny Rogers should sound like. But the Prince of Dirty Mind and Controversy didn’t exactly mesh with Nashville of the 1980s—what would the world have thought then if he released a country song? Giving that song to another voice freed him to fly elsewhere. Better known is his alias for “Manic Monday,” which charted at No. 2 for the Bangles, second only to Prince’s own smash “Kiss.” Here, Prince is “Christopher,” a reference to his character from his 1986 film Under the Cherry Moon. The song, triggered by a dream he wrote into the lyrics, is essentially a rewrite of “1999,” and Prince’s rendering of it here centers on a synthesized harpsichord and the psychedelic flourish of the song’s bridge, which sounds as if Alice just dropped in the rabbit hole. Most of the other tracks on Originals represent even greater gifts. Prince gave songs to Minneapolis’ great performers: Morris Day, Sheila E., Jill Jones, Apollonia, among others. By spreading out the credits, “he was creating the wave, but he made it seem like there was a lot of people doing that thing in Minneapolis, which was brilliant,” engineer David Z once said. To the press, Prince acted nonchalant. “I usually try to give up a groove to somebody if they ask me,” he said. These grooves are the dance-floor core of Originals. Prince’s version of “Jungle Love” is close to the rendition on the Time’s Ice Cream Castles and the Purple Rain soundtrack, down to the “oh-we-oh-we-oh” chorus, but embedded with his ad-libs (“If you’re hungry, take a bite outta me!”). Prince had showed up in the studio shirtless with one bandana around his neck and another tied on his ripped red pants, but he loosens up in the recording. “Somebody bring me a mirror!” you hear him shout midway through. He gets it in “Make-Up,” a torrid electric number that was fine on Vanity 6’s lone solo album but made surprising and transgressive by Prince, who voices the lyrics in robotic staccato bursts: “Blush. Eyeliner. Hush. See what you made me do.” It has the percussive electricity of Liquid Liquid and maybe a little Kraftwerk too, androgynous Prince at his most diva: “Smoke. A. Cigarette,” he retorts to an impatient lover. “I’m. Not. Ready Yet.” How wild that a chronicle of a lost era can feel so modern when all over it are musical markers of the ’80s: synths and drum machines and clap tracks and extended breakdowns and of course, sax solos. Nostalgia, even rendered fresh, works on the ear in invisible ways, as does the sequence of these songs. We careen between slow-burning love songs (witness Prince’s glorious falsetto over the heartbeat percussion of “Baby, You’re a Trip,” which Prince wrote for Jill Jones, about the time she snooped in his diary after he read hers) and more quintessential dance hits. “Holly Rock,” which he gave to Sheila E. for the Krush Groove soundtrack, is snappily upbeat, Prince punctuating the chorus with James Brown-esque flourishes (“I’m bad, good god!”) and a snarky taunt at the end: “Now try to dance like that,” he says. “Nothing Compares 2 U,” the best-known and most-loved of all the songs here, became a massive hit for Sinéad O’Connor, whose rendition was, in fact, a cover, not one of Prince’s gifts. Here, in its original incarnation, Prince turns it into a torch song for himself. He lets a love-worn raggedness occasionally creep into his voice, lets it tremble ever so, powered by the saxophone accompaniment of longtime Family and Revolution member Eric Leeds. The video shows a collage of Prince and his band running through stage choreography: dressed in a scarf worn as a backless shirt, or suspenders and white high-heeled boots, he delivers perfect splits, kicks, and spins. But the arrangement here is stark and lonely and beautiful, the closest you get to hearing Prince’s own pulse. Arriving at the end of this set of originals, and with the promise of hearing more from that vault, it becomes an affirmation too. Maybe all those flowers you planted in the backyard will bloom again.

Prince: Originals Review By Zach Schonfeld | June 17, 2019 | 10:00am Imagine giving away “Nothing Compares 2 U.” No really, think about it—what if your brain was such an astonishing repository of brilliant songs that you decided you could let that one go, just hand it to a less-established artist like some wild gesture of creative charity? For Prince, this was reality. He wrote the song, a great shimmering ballad of longing, in 1984, then gifted it to The Family’s debut album (which was largely an outlet for songs written by Prince), where it sat in obscurity for half a decade. When Sinéad O’Connor covered the song, it became a No. 1 hit, which begs the question: How many would-be No. 1 hits did Prince have hiding in plain sight? And what would it have sounded like if Prince had kept that song for himself? Originals, the new compilation from the Prince Estate (I emphasize “Estate,” because the late artist was not involved in this release and may or may not have hypothetically approved its existence), is a glimpse into an alternate universe where Prince did keep gems like “Nothing Compares 2 U” or “Manic Monday”—the breezy hit he wrote for The Bangles—for himself. Here we get 15 of Prince’s own versions of songs he wrote for other artists. Every fan knows that Prince left behind a bank vault containing thousands of hours of unheard music. Turns out some of that music has been heard, except performed by artists who are not Prince. The recordings on Originals are ostensibly demos (most of them tracked during the artist’s 1981-to-1985 creative burst), but Prince demos are not ordinary demos. They do not sound especially rough or unfinished because Prince was not just holding space for other musicians—he could play every instrument himself, and often did, as with 1980’s Dirty Mind. Plus, the artists he was writing for were often too dazzled, or too intimidated, by his creative vision to change his offering. Which explains why Prince’s recording of “Manic Monday” sounds virtually identical to the Bangles hit, from the effervescent keyboard riff to the infectious backing hook during the chorus; the key difference is Prince’s unmistakable voice floating over it all. (No wonder he gave it away; as good as the recording is, it is not very believable for Prince to be singing about the mundane grind of going to work on Monday.) I don’t need to tell you that the material is great—this is unheard music from Prince’s regal period, and it will be greeted by fans like rare jewels discovered in the wild. “Nothing Compares 2 U” sounds fully formed, as Prince brings the song to its dramatic swell of vocal harmonies and a wailing saxophone lead. Other god-level highlights include the thrilling space-funk of “Gigolos Get Lonely Too,” written for the Prince-associated funk group The Time, and the dreamy murmur of “Love… Thy Will Be Done,” sung in a syrupy falsetto that rivals Martika’s version of the song, which became a minor hit in 1991. Much like Martika (who hewed very close to this demo), Prince constructs the entire song around an unchanging bass and drum-machine pulse. It is vaguely reminiscent of the famous Linn LM-1 beat in “When Doves Cry,” and Prince’s overall knack for using repetition in revelatory ways. The other songs here (mostly written for Prince-associated acts like Sheila E. or Vanity 6) provide intriguing glimmers of what might have appeared on Prince’s own albums had he made different decisions. “Holly Rock,” a rousing funk-rock workout, could have replaced “It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night” as the full-band jam on Sign O’ the Times. “Sex Shooter” is dirty enough to have fit right in on 1999 (though it was actually recorded later and sung by Apollonia 6 in Purple Rain). “Baby, You’re a Trip” failed to become a hit for Prince’s backup singer Jill Jones, but Prince’s own version surely could have fit among the more gospel-y numbers on Around the World in a Day. (It also features a classic Prince scream.) Several of these tracks are stylistic exercises that don’t fit Prince as well as the artist he was writing for. He toys with crooning country-pop on “You’re My Love,” but there’s a reason he gifted the song to Kenny Rogers. “Make Up” (later recorded by Vanity 6) is an especially odd one, and the only real flop here. The song’s industrial synth refrain never progresses beyond mild irritation. (Think “Something In The Water [Does Not Compute],” but worse.) Originals offers a tantalizing glimpse of Prince as an artist whose creativity extended in so many directions at once that his own discography couldn’t contain it. As Susannah Melvoin told the New York Times recently, he had “a musical clairvoyance, this ability to project himself into you, as if he were another aspect of your artistic self.” He gave these songs away, but they could never lose his DNA.

|